Organizations use root cause analysis (RCA) to find the source of faults or problems in a manufacturing process. Although many factors could contribute to a problem, there’s usually just one forming the root cause.

To put it simply: if you can remove a factor in a problem and prevent it from occurring, that factor is the root cause of your problem. Although you can easily define a root cause, performing a root cause analysis is another matter.

This process requires several steps:

- Define the problem.

- Determine the duration of the problem and its impact.

- Identify contributing factors.

- Isolate the root cause using a fishbone diagram, the five whys method, or Pareto distribution.

- Develop a solution mitigating the root cause.

The process is lengthy and one that’s mission-critical to your organization. Any problem you don’t fix could recur, and any recurring problem might damage your reputation, incur fines or damages, or result in unplanned shutdowns.

However, getting a root cause analysis wrong might be the only thing worse than not going through the process at all. Getting it wrong means you’ve experienced a costly problem, went through the lengthy and expensive root cause analysis process, and spent money to fix the root cause. Except now you must do it all over again when the problem occurs a second time.

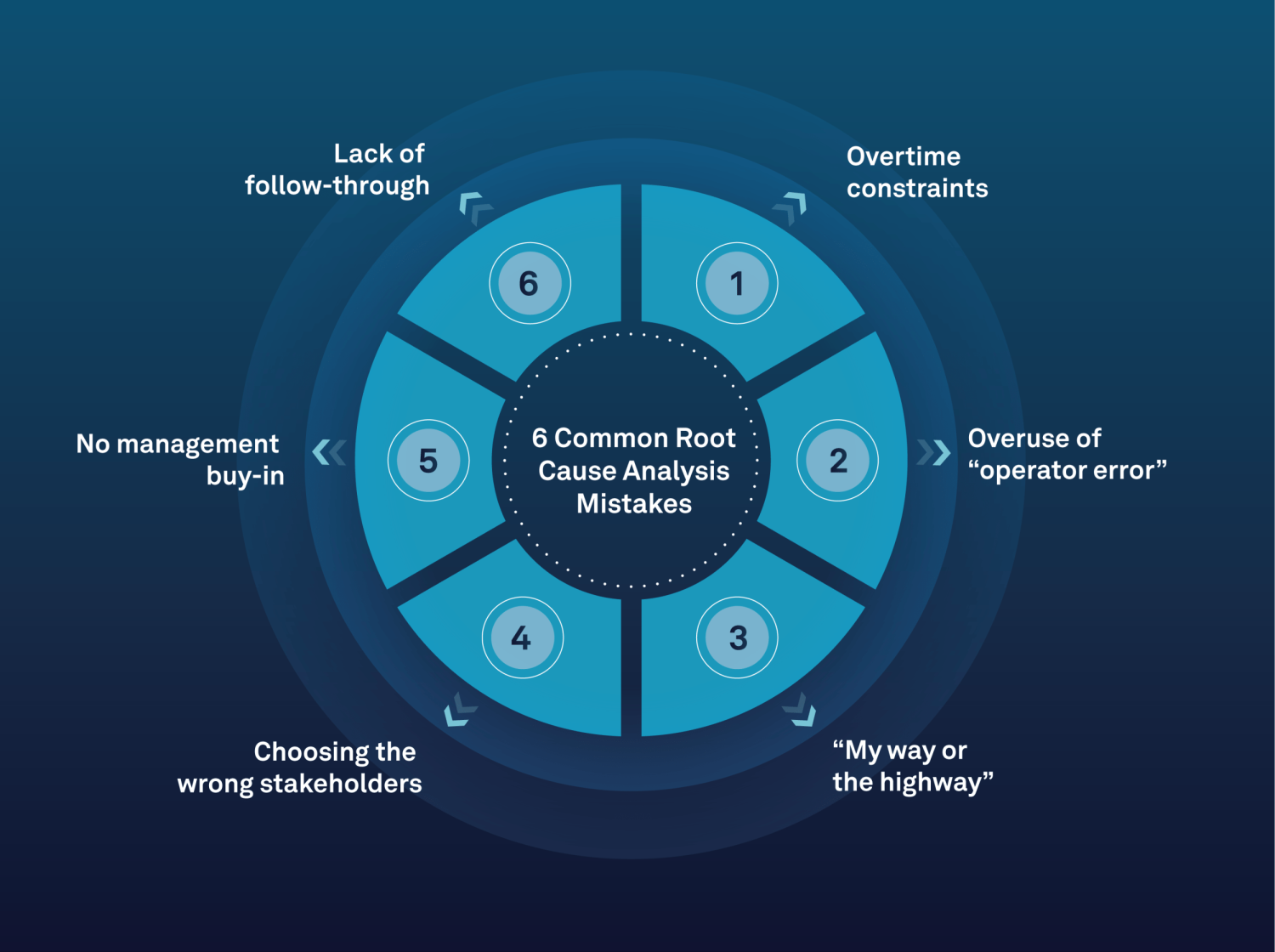

Root cause analysis mistakes are relatively common, but they don’t have to result in total do-overs. Instead, use the common mistakes below to analyze your processes and understand where errors are possible. Once you’ve done a root cause analysis of your mistakes, you’ll enjoy faster resolution times and more accurate problem-solving.

1. Overt time constraints

Time is not the enemy. Rushing through an RCA process means you won’t have enough time to review the relevant workflow, and it encourages the team to arrive at easy conclusions. Rushing through RCA isn’t just a problem—it’s a contributing factor to every other problem on this list. If someone gives you a near deadline for an RCA process, push back. As we’ve said, it’s almost not worth doing RCA if you’ll have to do it again.

2. Overuse of “operator error”

Look through the results of your previous RCA processes. If over 50% of them point to operator error, then you may be doing something wrong. In our opinion, operator error is a cop-out. You can always drill a little deeper to find out why that operator made that error.

For example: if an extra hour of training could have prevented a worker from committing an error, lack of training is the root cause. If a warning light should have gone off when the operator made the error, then the broken

warning light was the root cause. If the worker feels fatigued from a back-to-back shift, then that’s the root cause.

It’s worth mentioning that an overreliance on operator error diagnoses isn’t just lazy from an RCA standpoint. It’s also demoralizing to your workforce. They’ll start believing that problems affecting their job performance might never be fixed, only blamed on them.

3. “My way or the highway”

Regarding operator error, this mistake stems from a dogmatic belief that if someone doesn’t follow a process to the letter, then failing to follow that process is automatically the root cause of any problem. This theory is fallacious in two ways

- First, failure to follow a process might contribute to a problem, but it’s rarely the cause.

- Second, it ignores the possibility that the process itself might cause the problem.

Again, it’s always worth digging deeper if you find your RCA process leads you to this conclusion.

4. Choosing the wrong stakeholders

It often happens that organizations choose RCA team members because they’re the ones who have enough time to perform the process. That can be symptomatic because not enough time is being given to the RCA process (see problem one).

Choosing team members in this way also means there’s no guarantee they’ll be familiar with the processes under scrutiny during RCA. They’ll likely come to a shallower “operator error” or “my way or the highway” conclusion, not just because of a time limit but because they aren’t knowledgeable enough to dig deeper.

5. No management buy-in

Management should be well-informed about the purpose and importance of root cause analysis—and if they’re not, the process can suffer. Without buy-in, the RCA process may not be given the right time or the right team members to succeed. Or there might be pressure to wrap up the process before it reaches the correct conclusion. Always make sure management has your back when conducting RCA.

6. Lack of follow-through

Many RCA processes don’t go back and make sure that either:

- The problem they solved was the correct problem.

- The problem they solved stayed solved.

Both mistakes can result in recurring problems. The best hedge against this is to schedule a retrospective with your RCA team—perhaps one quarter out—to go back and check your work. This step is relatively simple and can save hours of wasted effort.

Work with ETQ to improve RCA

Here at ETQ, we take RCA seriously. That’s why we have an entire application dedicated to Corrective Action (CAPA) within our flagship QMS. This software lets you assemble the resources you need to conduct RCA, integrates the three primary analysis tools, and allows you to assess incidents within your organization as well as your RCA process.